Dr Fariba Behnia-Willison speaks about the Desert Flower South Australia and FGM at the AGES 2020 Conference

Why is addressing FGM important?

The practice of FGM has no medical justification and offers no health benefits to young girls and women. In reality, this practice can have devastating, life-long complications and in extreme cases, can be fatal.

Survivors of FGM demonstrate heightened risks of medical complications, including severe bleeding, problems urinating, cysts, infections, complications in childbirth, and increased risk of newborn deaths. Additionally, those who have been subjected to FGM commonly experience ongoing psychological trauma.1 Put simply, FGM is a violation of human rights.

FGM reflects the entrenched inequality between the sexes and can be considered an extreme form of discrimination against girls and women. The practice of FGM is in direct opposition to:

- The right to equality

- Freedom from discrimination

- Right to life and personal security

- Freedom from torture and degrading treatment

- The right to life

Whilst specialists and supports can reduce the physical and psychological damage of FGM, prevention must be the primary goal.

Background

FGM comprises all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia or other deliberate injuries to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.

FGM is not prescribed by religion and is almost always performed on girls aged between infancy and 15, and many before the age of 92. The procedure is usually performed by traditional practitioners using objects such as knives, razor blades, or broken glass.

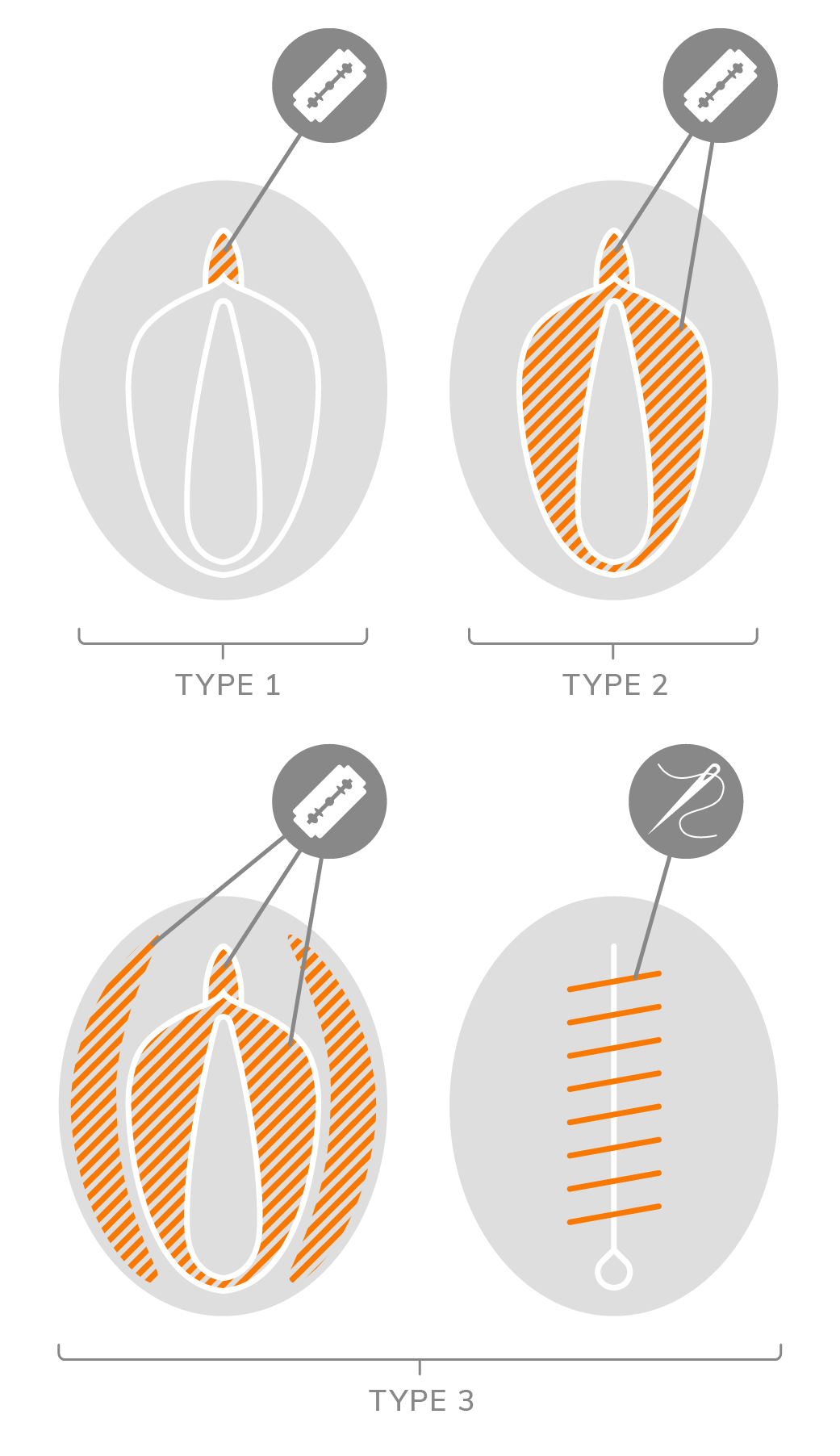

FGM is classified into four types:

- Clitoridectomy: This is the partial or total removal of the clitoral glans and/or the prepuce/clitoral hood.

- Excision: This is the partial or total removal of the clitoral glans and the labia minora, with or without removal of the labia majora.

- Infibulation: This is the narrowing of the vaginal opening through the creation of a covering seal.

- All other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes, such as pricking, piercing, incising, scraping, and cauterisation.3

More than 200 million girls and women alive today having been subjected to the practice of FGM and annually more than 3 million girls are estimated to be at risk of FGM. Thus, FGM is not a religious or region-specific concern, rather it is a global experience. The medicalisation of FGM is denounced by the World Health Organisation and any medical practitioner who practices any form of female genital mutilation is guilty of professional and criminal misconduct.

FGM in Australia

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare report that over 53,000 women and girls currently living in Australia, but born elsewhere, have undergone FGM. The Australian government views FGM as an abuse of human rights, and as a complex form of violence against women. FGM is prohibited nation-wide, as is transporting someone overseas to undergo FGM. FGM legislation has existed in Australia since the 1990s, though it remains relatively underutilised.

What could happen when a client realises that not everyone has been cut?

As FGM is still regularly practiced, and/or remains very hidden within certain cultures, families, and countries, women and girls who have experienced FGM may not acknowledge that they have endured a trauma and may not be aware that their vagina looks different to those who have not experienced FGM. As such, the sudden realisation of their condition and experience can be shocking, devastating, and destabilising.

As processing the experience (and implications) of FGM can be distressing for clients, it is imperative that health care providers act with the utmost respect. Health care providers must be conscious not to react with shock or surprise as these reactions can reinforce a client’s feelings of shame and stigma. Clinicians must work from a trauma-informed background and ensure that the principles of safety, respect, transparency, trust, control/choice, autonomy, and non-judgement are consistently implemented.

Desert Flower

Desert Flower South Australia works tirelessly to promote human rights and end all forms of discrimination and violence based on disability and gender.

If you are new to this area of practice, discussing FGM with a client may seem daunting. You may worry about saying the ‘wrong’ thing, or not having all the answers. However, remember more damage is done by not asking the question.

Many girls and women who have experienced FGM suffer in silence, at times too scared or too ashamed to talk about their experience. It is important that you develop your confidence in addressing this issue, to allow those who have suffered to be heard, validated, and treated.

As a clinician, you are in a privileged position to be able to identify and support women who may be struggling with FGM.

Why ask about FGM?

It is important to ask about FGM to:

- Ensure that you capture a thorough clinical picture to allow you to treat your client in the best and most effective way;

- Offer appropriate supports and treat the physical and psychological complications of FGM;

- Signpost to other health and community services, i.e., to determine and document FGM status for assisting with care and follow up;

- Ensure child safeguarding – discussing the issue may identify girls at risk and help keep them free from harm;

- Raise a topic that clients may be reluctant to discuss;

- Enable a client to receive information about changes she may experience after de-infibulation;

- Discuss de-infibulation and re-infibulation with her before labour.

How do I discuss FGM with my clients?

Discussions surrounding FGM can be complex and we must always consider the rights, values, and perspective of our clients. As clinicians, we must remove our own biases and do what is best for the wellbeing of our clients. It is important to create a safe space for your clients, so they feel supported and cared for, and to ensure they continue to seek the help they need and deserve.

Remember that some women want to treat the symptoms, while others see FGM health consequences as usual. Take the time to pick up cues from your patient as to how she feels about living with FGM. For example:

- Does she feel ashamed? Indifferent?

- Does she appear comfortable or nervous discussing health consequences?

- How does she refer to FGM as herself?

The tips below are a starting point for navigating a difficult topic.

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare report that over 53,000 women and girls currently living in Australia, but born elsewhere, have undergone FGM. The Australian government views FGM as an abuse of human rights, and as a complex form of violence against women. FGM is prohibited nation-wide, as is transporting someone overseas to undergo FGM. FGM legislation has existed in Australia since the 1990s, though it remains relatively underutilised.

Do's

- Use the exact words your client uses to describe her experience with FGM.4

- Ask your client if she is willing or able to talk about her FGM/C.4 Always provide your client with the choice to provide as much or as little information as she feels comfortable with.

- Provide a professional interpreter/translator.5 Use a female interpreter where possible and avoid using family members to interpret.

- Limit the number of providers in the examination room with her.

- Use a nonjudgmental tone when discussing health consequences.6

- Keep an open mind about how your patient feels about life with FGM. Do not project your judgements of biases onto your client.

- Ask your client if she would like someone to accompany her.7

- Make FGM/C care a recurring part of your client’s routine visits to help her overcome embarrassment.8

- Provide resources and information packs for your client to take home – these need to reduce shame and stigma, normalise help-seeking and be easy to understand and simple to read.

- Explain why some requests may not be legally or ethically possible (i.e., re-infibulation following de-infibulation is outlawed in some countries).9

- Give referrals to specific mental health services or other specialised physicians such as adolescent gynaecologists and urogynecologists.10

- Recognise that all types of FGM are harmful physically and/or psychologically. No hierarchy can be made in the pain and the trauma caused by FGM.

- Women and girls who have undergone FGM are survivors, not victims. Acknowledge survivors’ resilience and strength.

- Tell positive stories as a way of promoting FGM abandonment. Show that change is possible and can be inspiring to others.

- Recognise FGM abandonment as a feminist issue. FGM aims at controlling women’s bodies and sexualities. Both women and men play a role in the continuation or abandonment of the practice.

- Use comprehensive, respectful, and non-stigmatising language.

- Let people own their narrative and understand that every survivor has a different experience.

- Let survivors tell you who they are and what they do today. Listen and respect them.

- Be aware of your own responses and reactions the first time you examine a woman or girl who has undergone FGM to ensure she does not feel uncomfortable or different.

- Record FGM Status: Record FGM status on the birth notification to ensure the maternal and child health nurse is mindful of any ongoing health concerns, and also to ensure follow-up of daughters.

Don’ts

- Do not make clients re-live their trauma.

- Don’t use shocking images that risk causing re-traumatisation of FGM survivors and of affected communities. Don’t use graphic images or details such as blades or blood.

- Don’t fuel hate speech by using words such as ‘barbaric’, ‘disgusting’, ‘savage’ that are offensive and judgmental for affected communities. Do not use sensationalising headlines or terms.

- Don’t romanticise or re-write a survivor’s story.

- Don’t assume that everyone in an affected community feels the same way about FGM.

- Don’t portray FGM with a sense of cultural otherness, that reinforces stereotypes and misunderstandings.

- Don’t forget that many people and communities have abandoned FGM, and cultural norms change over time. Change is possible and is happening.

- Don’t portray survivors as victims.

- Don’t assume you already know their story, don’t assume all stories are the same.

- Don’t minimise survivors’ experiences when they tell their stories.

Questions and Language

When talking with a survivor of FGM, use language appropriate to the clinical setting.

Remember to take a moment to signpost why you are asking these questions, so they do not come across as irrelevant or intrusive.

For example:

- Sometimes your symptoms can be caused by something called FGM or female circumcision. It is important to know if a pregnant woman has had anything done which might affect her when she gives birth, such as being cut or closed down below.

- Before I examine you, I just need to check if you’ve ever had any operations or been cut?

You could ask:

- Around the world some communities practice female circumcision or cutting. Does this happen in your community?

- Have you been cut down there?

- Have you had traditional cutting?

- Have you been circumcised? (and point to your lap area)

- Have you been cut/circumcised/closed?

- Have you ever had any operations or been cut on your vagina/genitals/down below?

- Has anything ever been done to you to change your appearance ‘down below’?

Then you could ask:

- “What term do you use to refer to traditional cutting or circumcision?” You can then use the term that the client feels most comfortable using.

Dr Raymond’s 4Cs

(Dr Sharon Raymond 2015)

Dr Raymond provides a clear framework for assessment.

For all women and girls, ask the first 2 questions:

- Do you come from a community that practices cutting?

- Have you or any member of your family been cut?

- For children, ask: ‘Does anyone intend to cut you or anyone you know?’

- For females who are pregnant or have daughters, ask: ‘Do you or anyone you know intend to have your daughter(s) cut?’

For any woman or girl at risk of FGM follow your local Safeguarding Procedures.

When discussing FGM it is important to:

- Avoid making assumptions and judgements

- Be sensitive to the intimate nature of FGM.

- Use simple language and ask straightforward questions.

- Be direct when assessing its impact by asking questions such as:

-

- ‘Do you think the circumcision has caused you any problems? Do you ever think about it?’

- ‘Do you experience any pain or difficulties during intercourse?’

- ‘Do you have any problems urinating?’

- ‘Have you had any difficulties in childbirth?’

Make the woman or girl feel comfortable and ensure she knows she can come back if she wishes.

FGM Management

For women or girls suspected or known to have had FGM, management falls into 3 broad categories:

- Management of physical symptoms

- Management of psychological symptoms

- Safeguarding by having policies, procedures and practices to ensure all children are safe.

As clinicians, you must be aware of the potential risks to young women and girls. Asking about FGM is vital to protect women and girls and to aid in the prevention of FGM.

You must inform the woman or girl that FGM is illegal in Australia and that the law is there to help and protect women and girls. However, it is essential that your patient is in a mental state that will enable them to take this information on board. Consequently, ensure you choose the most appropriate time on the patient’s help-seeking experience to discuss this with them.

Such conversations are imperative because:

- This can then prevent FGM from occurring in the future to her daughters;

- They enable families to receive information about the legalities and health consequences of FGM;

- Not all families want their daughters to undergo FGM, but they may be under pressure to have their daughters circumcised.

Questions to ask include:

- How do you view circumcision?

- Do you think it is important for girls? Why?

- Are you aware of any harmful effects of circumcision?

- Are you worried about your daughter if she is not circumcised?

- Is there anyone else in the family who may feel strongly that circumcision is important?

- Are you planning a trip home soon? Are you expecting any family visitors from home?

- How can we support you to protect your daughter?

It is important to include a question about the FGM status of the woman or girl in your assessment or first contact meeting.

“FGM needs to be integrated into screening, pap smears and for when patients are preparing for children. There is a lot of self-blame and embarrassment. For many women, this was not a choice. For many women talking about it was not common.”

VICTORIA

Child protection in Victoria after hours number to call is: 131278

TASMANIA

To notify child protection in Tasmania call

1300 737 639

QUEENSLAND

Dept of Communities, Child Safety and Disabilities

1800 177 135 or (07) 3235 9999

SOUTH AUSTRALIA

South Australian Child Abuse contact Child Abuse Report Line on 131 478

NSW

The NSW Child Protection Helpline on

132 111 (TTY 1800 212 936)

for the cost of a local call, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week

Treatment for the psychological impacts of FGM

Desert Flower South Australia want to ensure clients can have recovery across all areas of their life, both physically and emotionally. To do this, they have engaged experts from PsychMed to join their team. PsychMed has a team of experts in trauma work to help clients process their trauma and have inner peace.

In addition to pain and discomfort associated with FGM, women have many different emotional responses to the memories of FGM or cutting. This emotional distress is a normal reaction to the mutilation clients have experienced. FGM can leave clients feeling overwhelmed and can trigger intense emotional responses. These, in turn, can affect different parts of a client’s life.

Sometimes women describe the following symptoms after FGM, all of which are treatable:

- Flashbacks or frequent nightmares of the mutilation

- Feeling sensitive to noise or to being touched

- Always expecting something terrible to happen

- Not remembering periods of their life

- Feeling numb, detached, or daydreaming

- Lack of concentration, irritability, sleep difficulties

- Excessive watchfulness

- Feelings of anxiety, anger, sadness, guilt, shame, or depression

For many women, the world can be a frightening place. At PsychMed, our team uses specific therapies that are proven to be effective in helping people get better from these emotional symptoms. Our specific treatment is called Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) which allows clients to process the emotional scars of FGM/cutting. We can help clients to slowly examine and change the unhelpful thoughts and feelings related to their trauma, themselves, others, and the world. An essential part of treatment is addressing ways of thinking that might keep the client stuck and get in the way of their recovery.

Through this therapy, PsychMed clinicians can help to reduce levels of distress, anxiety, anger, guilt, and shame, so clients can have a better quality of life.

Remember and believe you have the right to celebrate your progression into womanhood without the mental and physical scars of FGM. If you would like support from PsychMed’s trauma program and clinicians, please call PsychMed on 7444 4260 or email ADL@psychmed.net.au and view our website here: https://psychmed.com.au/trauma-services/

Resources

World Health Organisation

This includes training videos that are allowed to be shared and a downloadable guide to communication.

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240041073

References

1 World Health Organization. (2016, June 1). Health risks of female genital mutilation (FGM). Available at: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/fgm/health_consequences_fgm/en/

2 UN General Assembly, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 10 December 1948, 217 A (III), available at: http://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/

3 World Health Organization, Department of Reproductive Health and Research (2008). Eliminating Female Genital Mutilation. An interagency statement – OHCHR, UNAIDS, UNDP, UNECA, UNESCO, UNFPA, UNHCR, UNICEF, UNIFEM, WHO. Available at: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/fgm/overview/en/

4 World Health Organisation, Care of Girls & Women Living with Female Genital Mutilation: a Clinical Handbook, 2018: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272429/9789241513913-eng.pdf?ua=1

5 Balfour, J., Abdulcadir, J., Say, L., & Hindin, M. J. (2016). Interventions for healthcare providers to improve treatment and prevention of female genital mutilation: a systematic review. BMC health services research, 16(1), 409. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1674-1

6 Costello S. (2015). Female genital mutilation/cutting: risk management and strategies for social workers and health care professionals. Risk management and healthcare policy, 8, 225–233. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S62091

7 World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/gender/other_health/teachersguide.pdf

8 Comfort Momoh, Shamez Ladhani, Denise P. Lochrie, Janice Rymer (2003), Female genital mutilation: analysis of the first twelve months of a southeast London specialist clinic, BJOG, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2001.00036.x

9 Adelaide A. Hearst, MD, and Alexandra M. Molnar, MD (2013), Female Genital Cutting: An Evidence-Based Approach to Clinical Management for the Primary Care Physician, Mayo Clinic, 88(6):618-629, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.04.004

10 Mishori R, Warren N, Reingold R. (2018), Female Genital Mutilation or Cutting. Am Fam Physician. 1;97(1):49-52. PMID: 29365235.